Christianity as philosophy and athletic struggle

Plato’s Protocol Series, 7

I have fought the good fight,

I have finished the race,

I have kept the faith. - St. Paul, 2 Timothy 4:7

With the advent and spread of Christianity in the first and second century A.D. we start to see the assimilation of Greco-Roman philosophy to Christianity. Christian writers defending and articulating Christian beliefs in a pagan world were referred to as the Apologists. These included early scholars, philosophers and theologians like Justin Martyr, also known as Justin the Philosopher, Clement of Alexandria, Origen and Irenaeus.

Justin Martyr is a great example of someone who represents this convergence of Greco-Roman philosophy and Christianity. Born into a Greek family in 90 A.D. he studied the philosophies of Stoicism and met philosophers from the Peripatetic school of Aristotle and Pythagorean school but was turned off by both of them. He subsequently adopted Platonism before converting to Christianity.

“Reason dictates that those who are truly pious and philosophical should honor and love only the truth, declining to follow opinions of the ancients, if they are worthless.” - Justin Martyr

Christianity as THE philosophy

The Christ Pantocrator of the Deesis mosaic (13th-century) in Hagia Sophia (Istanbul, Turkey). Wikimedia

There was a widespread Christian tradition that characterized Christianity as a philosophy. Justin Martyr called Christianity ‘’our philosophy.’’ Origen and later the Cappadocian Fathers (Basil of Caesarea, Gregory Nazianzen and Gregory of Nyssa) would refer to Christianity as the ‘’complete philosophy’’ and ‘’the philosophy according to Christ.’’ These apologists and theologians didn’t believe it was one of another philosophy like the other Hellenistic schools; they considered it the philosophy. 1

The identification of Christianity with true philosophy appropriated and integrated classical Greek philosophical concepts for Christian purposes. ‘’Each Greek philosopher, they wrote, had possessed only a portion of the Logos, whereas the Christians were in possession of the Logos itself, incarnated in Jesus Christ. If to do philosophy was to live in accordance with the law of reason, then the Christians were philosophers, since they lived in conformity with the law of the divine Logos.” 2 Here Logos was intentionally used to bridge Greek philosophy with Christian theology. Literally meaning word, reason and speech, in ancient Greek, the Stoics expanded Logos to mean a divine and rational principle that governs the entire universe.

The ‘’Hellenization’’ of Christianity not only influenced the emerging Christian assimilation of philosophy but also led to the absorption of the Greco-Roman philosophical spiritual practices. As mentioned in lesson 6 attention and vigilance (prosoche) on oneself was the philosophical attitude par excellence. For Basil, the Cappadocian theologian, who we met in lesson 5, the philosophical idea of self-awareness meant paying attention to the ‘’beauty of our souls.’’

In a sermon, Basil of Caesarea took a passage from Deuteronomy, combined with wisdom from Platonic and Stoic traditions, to focus on the importance of self-awareness, from a Christian perspective.

Only be careful, and watch yourselves closely so that you do not forget the things your eyes have seen or let them fade from your heart as long as you live. Teach them to your children and to their children after them. - Deuteronomy 4:9

For Christians, St. Basil instructs his fellow Christians, “attention to oneself consists in awakening the rational principles of thought and action which God has placed in our souls.” By doing this we can correct the judgments we bring upon ourselves, as we ‘’watch ourselves.’’

If we think we are rich and noble, we are to recall that we are made of earth, and ask ourselves where are the famous men who have preceded us now. If, on the contrary, we are poor and in disgrace, we are to take cognizance of the riches and splendors which the cosmos offers us: our body, the earth, the sky, and the stars, and we shall then be reminded of our divine vocation.” - St. Basil 3

It’s not hard to hear the wisdom of the Greco-Roman philosophers, especially the Stoics, in this Christian sermon.

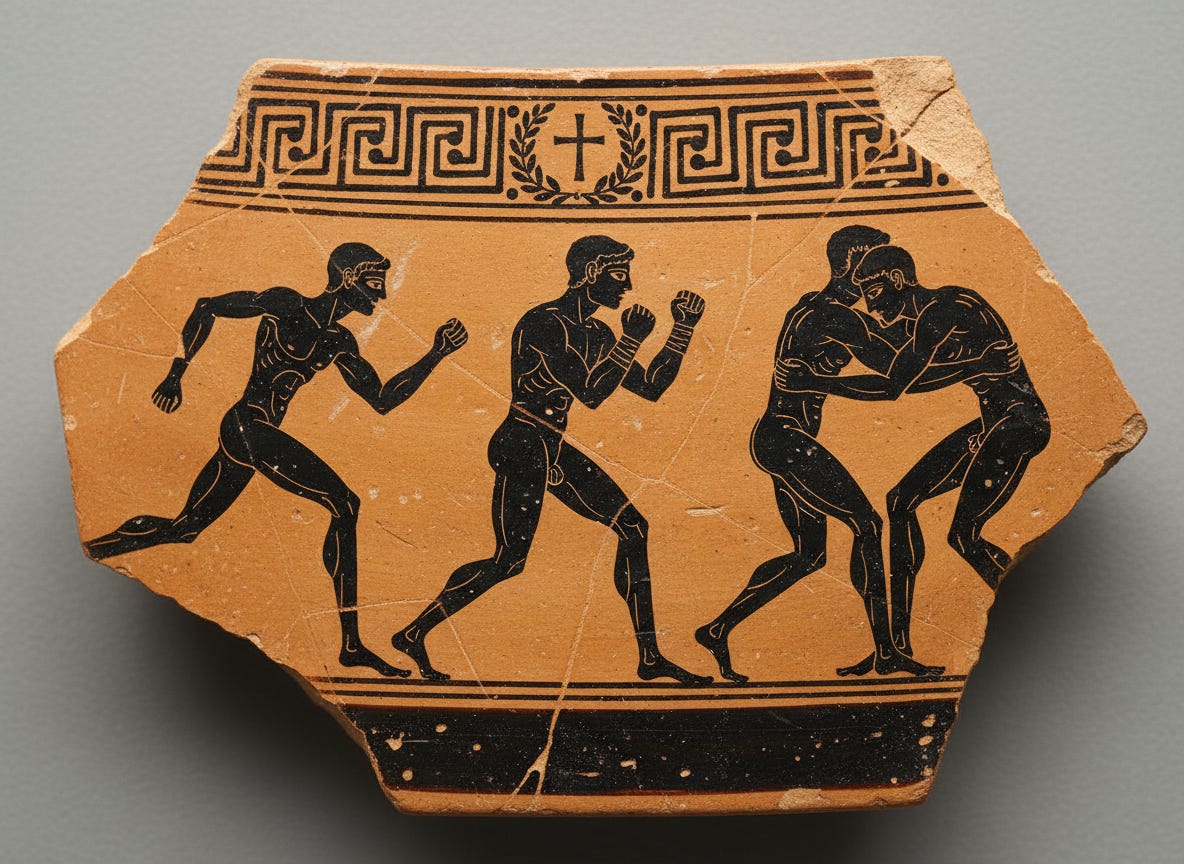

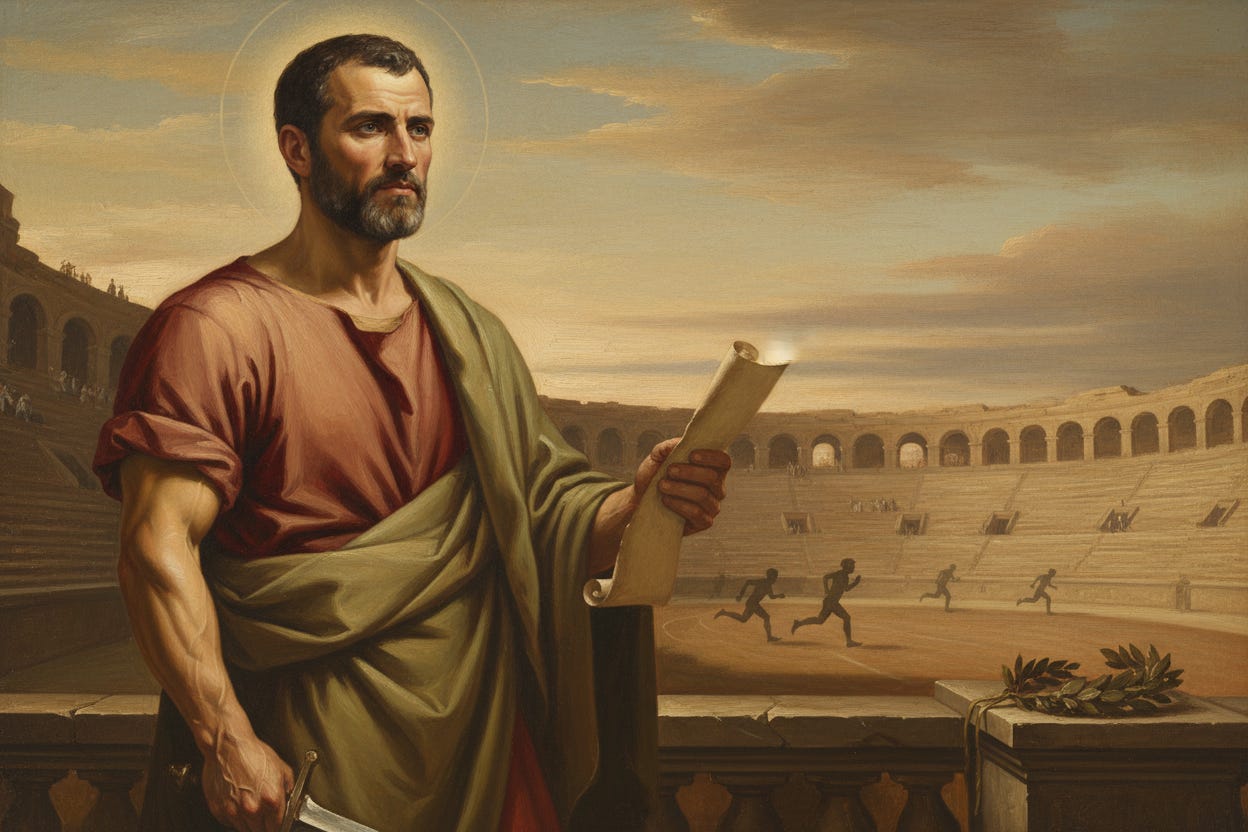

St. Paul and the Athletic Discipline of the Spirit

The practice of askesis, a disciplined training of the soul toward virtue, finds a remarkable parallel in the writings of St. Paul. Drawing from the athletic culture of the Greco-Roman world, Paul employed vivid sports metaphors to convey spiritual truths and inspire Christians to live disciplined, purposeful lives. Like the Greek philosophers before him, Paul recognized the transformative power of struggle and perseverance, using the language of athletic competition to illuminate the spiritual journey.

24 Do you not know that in a race all the runners run, but only one gets the prize? Run in such a way as to get the prize. 25 Everyone who competes in the games goes into strict training. They do it to get a crown that will not last, but we do it to get a crown that will last forever. 26 Therefore I do not run like someone running aimlessly; I do not fight like a boxer beating the air. 27 No, I strike a blow to my body and make it my slave so that after I have preached to others, I myself will not be disqualified for the prize. - 1 Corinthians 9:24–27 4

St. Paul’s letters frequently draw from the imagery of the race, the boxing ring, and the wrestling match to paint a picture of the Christian life as a contest of the soul.

Running the Race: In 1 Corinthians 9:24–27, St. Paul compares the Christian life to running a race, urging believers to run with intention, perseverance, and the aim of securing an imperishable crown. This metaphor highlights the need for focus and endurance.

Boxing and Discipline: St. Paul likens his own spiritual discipline to a boxer’s training, remarking that he does not fight aimlessly but with clear purpose. This imagery underscores the effort and self-control required to live a virtuous life.

Wrestling Against Evil: In Ephesians 6:12, St. Paul depicts spiritual warfare as a wrestling match, a direct struggle against powers of darkness. Here, the physicality of wrestling symbolizes the intimate, personal nature of spiritual conflict.

Athletic Rules and Obedience: In 2 Timothy 2:5, St. Paul compares the Christian life to an athlete competing under strict rules, emphasizing the importance of adherence to God’s will in the pursuit of spiritual victory.

The Spiritual Gymnasium

In the same way that Socrates and Plato mentored students in the philosophical gymnasium, St. Paul called Christians to a spiritual gymnasium—a life of disciplined training in faith and virtue. For St. Paul, this training was not aimed at fleeting worldly rewards but at an eternal crown (1 Corinthians 9:25).

Through practices like prayer, fasting, and acts of charity (alms giving), believers engaged in their own rigorous spiritual training, strengthening their souls in the pursuit of holiness and alignment with God’s will.

Just as athletes endure hardship and discipline to achieve physical excellence, Christians are called to embrace self-control, perseverance, and sacrifice to cultivate their spiritual lives. This training required not only individual effort but also a communal aspect, as believers encourage one another in their shared journey toward salvation.

The spiritual gymnasium, as envisioned by St. Paul, was a place of transformation where the inner struggles of faith were met with steadfast dedication. Here, the “contest” was against sin, temptation, and the challenges of the world, with victory defined not by personal glory but by a life fully devoted to God. The ultimate goal was the sanctification of the soul—a condition of virtue and grace made possible through the power of the Holy Spirit and the believer’s commitment to walking in faith. Paul’s metaphor inspires Christians to approach their spiritual lives with the same intentionality and discipline as athletes preparing for the race of their lives.

Why did St. Paul use Athletic Metaphors?

St. Paul’s choice of athletic imagery was neither accidental nor superficial. These metaphors were deeply resonant with his audience for several reasons:

Relevance to his audience: St. Paul’s use of athletic imagery resonated with the Greco-Roman culture of his time, where sports and athletic competitions were highly valued. This made his teachings more relatable and understandable to his readers.

Illustrating spiritual discipline: St. Paul used athletic metaphors to emphasize the importance of self-discipline, rigorous training, and perseverance in the Christian faith. He compared the dedication of athletes to the commitment required in following Christ.

Emphasizing purpose and focus: Through these metaphors, Paul encouraged believers to maintain a clear goal and stay focused on their spiritual journey, just as athletes remain focused on winning their competitions.

Demonstrating the importance of rules: St. Paul used athletic analogies to highlight the significance of following God’s instructions, comparing it to athletes adhering to competition rules

Conveying the concept of reward: The idea of a prize or crown awarded to victorious athletes was used to illustrate the eternal rewards awaiting faithful Christians.

Explaining his own ministry: St. Paul employed these metaphors to describe his own dedication and struggles in spreading the Gospel, likening his efforts to those of an athlete in training and competition.

By using athletic metaphors, St. Paul effectively communicated complex spiritual concepts in a way that was accessible and meaningful to his audience, drawing parallels between the physical discipline of sports and the spiritual discipline required in the Christian life.

In the next lesson, we will look at the original meaning of the word athlete and how it can serve as inspiration for our way of life.

Notes

Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, p. 129

Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, p. 129

Pierre Hadot, Philosophy as a Way of Life, p. 131

New International Version (NIV)