The Great Books: The lifelong reading list of the 300 best books from the Western Tradition

Create your own ‘’unread library" to learn the Great Lessons, from the Great Books to become Great and Good (aka virtue)

Read not the Times. Read the Eternities. Knowledge does not come to us by details, but in flashes of light from heaven.

- Henry David Thoreau, Life Without Principle

Read good books. Read great books. Read The Great Books!

Reading the Great Books is the most unique element of my classical approach to personal growth. If you read the Start Here article - How Plato, the US military and C.S. Lewis helped me find the missing piece to my daily workout - you will see how I was inspired by Plato’s cultural program, in his Republic, to complement my physical workout. I was further inspired by the Marines’ idea of a professional reading list to develop a ‘’5,000 year old mind,’’ and C.S. Lewis’ recommendation to alternate between old and new books.

But what are these foundational classic books to read, why are they so important for us and how do you find a working list to use in your ‘’cultural workout?’’

Let’s take a deep dive into some key training material to help you strengthen your cultural muscles.

The original canon of ‘’admitted’’ and ‘’included’’ Greek classics

The idea of a literary ‘’canon’’ was a Greek invention.

The British-born classical scholar and historian Bernard Knox explains the history of the idea of a canon in his book The Oldest Dead White European Males and Other Reflections on the Classics. Writing in 1993 Knox states that the ‘’’source’’ and ‘’vital core’’ of the so-called cannon were classics of Greek literature:

“At the heart of the so-called canon, it’s source and still after all these years it’s vital core, are the masterpieces of classical Greek literature: the epic poems of Homer; the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides; the comedies of Aristophanes; the histories of Herodotus and Thucydides; the odes of Pindar and the remnants of the other lyric poets, Sappho their brightest star; and the dialogues of Plato.’’ - Bernard Knox

How did the Greeks come up with this list of writers and their works?

The original canon was created by scholars of the Alexandrian library, in the third and second centuries BC. This era was characterized by the spread of Greek culture and language (Koine Greek) throughout the Mediterranean and Near East, including Egypt under the Ptolemaic dynasty. The library flourished in the Hellenistic period following the conquests of Alexander the Great, who founded the city of Alexandria in 332 BC. It was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, dedicated to the Muses, the goddesses of arts. The Great Library of Alexandria stood as a symbol of ancient Greek intellectual ambition and cultural fusion in the Hellenistic world.

The Greek scholars and critics of the Alexandrian library ‘’established select lists of the principal figures in each literary genre,’’ Knox tells us. “Homer and Hesiod were singled out from the immense body of early epic poetry as the great masters.” The Alexandrian scholars also chose nine lyric poets, which included Pindar and Sappho. They chose play writers from the tragic stage - such as Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. They also chose historians, philosophers, and even orators.

Although ‘’canon’’ is an ancient Greek word (meaning a carpenter’s rule) it wasn’t the word that the Alexandrian scholars used. (Canon was first used in 1768 by the German scholar David Ruhnken). The Greek word these scholars used was hoi enkrithentes, which meant ‘’the admitted’’ or ‘’the included.’’ The Romans, as they have always done, appropriated the Greek word and expressed the idea with the word classicus, a Latin word derived from their political institutions, meaning ‘’belonging to the highest class of citizens.’’

This first ‘’canon’’ was not merely an academic exercise, as we probably envision it in our modern times. In this ancient time period book production was a time-consuming business of hand-copying on fragile and perishable papyrus scrolls. If these books were not ‘’admitted’’ or ‘’included’’ they were likely to disappear as there were no new copies created.

During this time of foreign invasion and civil wars there was great turmoil in these classical civilizations. The majority of Greek literature has been lost to us, such as the majority of the nine lyric poets. Knox explains to us how the foundational great books survived:

‘’Only those works transferred to the more durable (and expensive) material of parchment could survive, and in what was now a Christian world the pagan authors preserved were those thought necessary for the schooling of the young - a restricted version of the original canon: Homer, Hesiod, Herodotus, Thucydides; seven tragedies each for Aeschylus and Sophocles, ten for Euripides; eleven comedies of Aristophanes; and, partly no doubt because of the influence of Neoplatonic philosophy on the Christian theologians, all of Plato, and much of his successor Aristotle.”

Why read the Great Books: Cultivate Virtue and Human Excellence

Real literature is something much better than a harmless instrument for getting through idle hours. The purpose of great literature is to help us to develop into full human beings. - Russell Kirk

The Great Books are not museum pieces; they are training partners.

When you read Homer, Sophocles, Plato, Augustine, Dante, Montaigne, Tocqueville, Austen, and Dostoevsky, you step into a gym for the soul where your faculties are put under disciplined stress: memory, attention, imagination, reason, courage. The result is not trivia or mere “context,” but mental muscle—habits of mind that can withstand confusion, fashion, and flattery. Plato (and Socrates) teaches you to ask the question behind the question. Thucydides trains your organizational eye to see consequences before they arrive. Marcus Aurelius steadies your hands when duty feels heavy.

These books do not simply entertain; they tutor your powers and form your character, helping you become the kind of person who can act—calmly, decisively, prudently—when it actually counts.

They also give you a “5,000-year-old mind” with a spine. C.S. Lewis warned that every age has its own blind spots; the antidote is alternating old and new books so the past can correct the present. The canon—the “admitted” and “included” classics—functions like a leadership council across centuries. You gain second sight: patterns in human nature, wisdom, love, loyalty, pride, decay, renewal. Read Herodotus or Aristotle and you learn to separate permanent things from passing fashions.

This is the classical path to excellence: to cultivate virtue by companionship with the best minds, to apprentice yourself to greatness until its standards become your own. In a culture of hot takes and short memory, the Great Books reforge a long view—and with it, judgment.

Learning from the Great Books is a form of leverage. Very few people learn from the classics or history. But true learning is not just memorizing information. It’s changing behavior. That’s where the struggle (agon in Greek) comes from and the need to consider this type of reading more than an act of leisure but rather a real workout. Reading the Great Books well has the power to cultivate virtue.

Most importantly, Great Books reading is a way of life, not a one-off activity. Like the Marines’ professional reading list, it builds a cadence: steady, deliberate, cumulative. You read to become more capable in your virtuous vocation, more loyal in your friendships, more patient in your trials. You read to recover words for realities our age forgets—honor, magnanimity, piety, duty—and to test them against the hardest cases.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” — James Baldwin

The classics won’t do the pushups for you, but they will intellectually spot you, coach your form, and refuse to let you skip intellectual leg day. Over time, they cultivate the inner posture of the traditionally minded leader: principled, resilient, oriented to the good—and ready.

Assembling a Great Books list

In the case of good books, the point is not to see how many of them you can get through, but rather how many can get through to you. - Mortimer Adler

Where does one go to find a definitive list of the Western Canon?

I found it especially helpful to focus on two credible sources: 1/ scholars who have written on the importance of the Western Canon and created their own lists and 2/ universities who specialize in teaching a Great Books program.

I began with Mortimer Adler (1902–2001) a 20th century American philosopher and educator. He taught at the University of Chicago, helped found the Aspen Institute, and was a long-time editor and guiding force behind Encyclopaedia Britannica’s editorial projects. He saw the Great Books as an ongoing “Great Conversation” in which authors respond to one another over centuries. Reading them trains people to join that conversation thoughtfully. In 1952 he wrote Great Books of the Western World ( with Robert M. Hutchins): A curated 54-volume set published by Encyclopaedia Britannica. In addition he wrote How to Read a Book (with Charles Van Doren in later editions). In this second book he included A Recommended Reading List, as an appendix:

All of these books are over most people’s heads—sufficiently so, at any rate, to force most readers to stretch their minds to understand and appreciate them. And that, of course, is the kind of book you should seek out if you want to improve your reading skills, and at the same time discover the best that has been thought and said in our literary tradition.

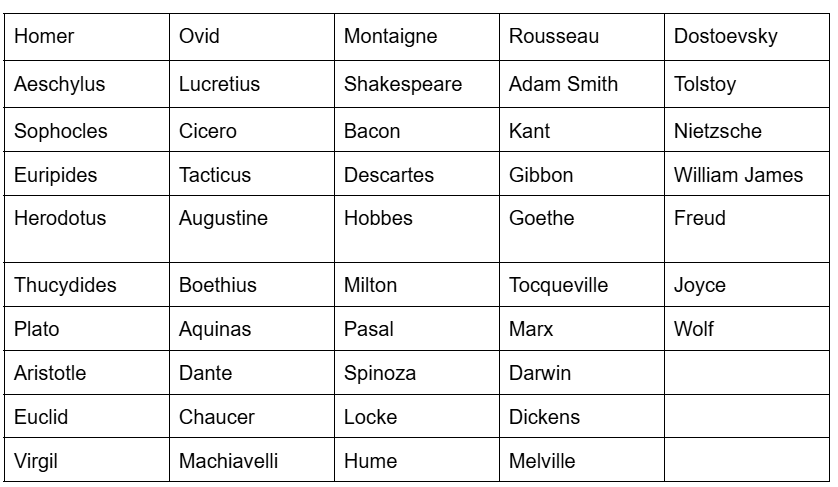

Here is Adler’s list of 137 authors, from Homer to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn.

Another take on the Great Books was from Harold Bloom (1930 - 2019). Bloom was an influential American literary critic and professor of Humanities at Yale University and later an English professor at New York University. In 1994 he directly stepped into the Great Conversation with the publishing of his book The Western Canon: The Books and Schools of the Ages.

The Western Canon is a landmark book in literary criticism. Bloom directly defends the concept of a Western literary canon, identifying 26 key authors as central to the Western tradition. Bloom’s stated goal was to ‘’confront greatness directly.’’

Bloom argues that true greatness in literature comes from originality and aesthetic strength. An author enters the canon not through ideology but through an innovative mastery of language, cognitive power, and a necessary “strangeness” that challenges readers. He describes the impact of reading a Great Book for the first time.

‘When you read a canonical work for a first time you encounter a stranger, an uncanny startlement rather than a fulfilment of expectations.’

For my Great Books planning, Bloom also created his own complete list of a Western Canon. Here is a list of Bloom’s full canon.

The final source for our Great Books inventory is St. John’s College in Annapolis, Maryland. This school is known for its distinctive Great Books curriculum which was first started in 1937. This unique academy program emphasizes the study of classic works of Western civilization. Every student reads a very large, fixed sequence across four years. According to its site :

The reading list at St. John’s includes classic works in philosophy, literature, political science, psychology, history, religion, economics, math, chemistry, physics, biology, astronomy, music, language, and more.

St. John’s graduate Salvatore Scibona wrote about the impact the Great Books program had on him:

The college’s curriculum was an outrage. No electives. Not a single book in the seminar list by a living author. However, no tests. No grades, unless you asked to see them. No textbooks—I was confused. In place of an astronomy manual, you would read Copernicus. No books about Aristotle, just Aristotle. Like, you would read book-books. The Great Books, so called, though I had never heard of most of them. It was akin to taking holy orders, but the school—St. John’s College—had been secular for three hundred years. In place of praying, you read.

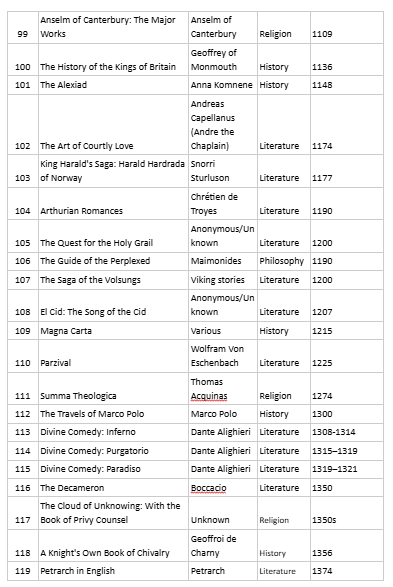

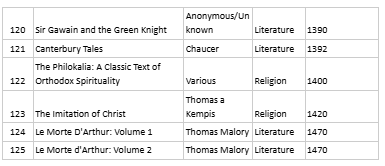

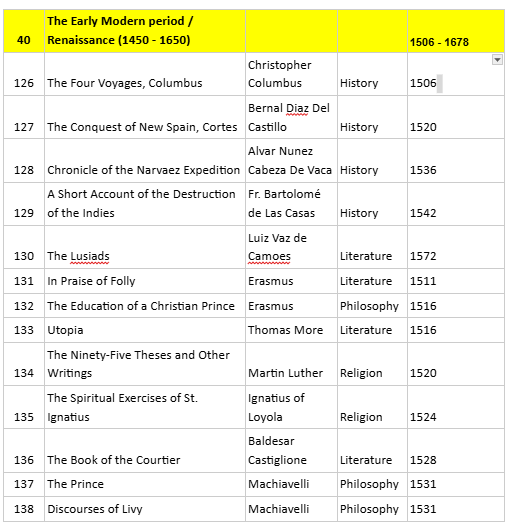

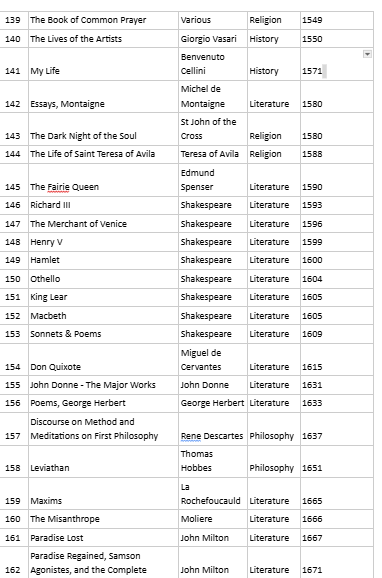

What did I get out of these Great Book lists?

All these lists - Morimter Adler, Harold Bloom and St. John’s College - provide a great starting point. There are 47 writers who are common to all three lists. As you can see below, it comprises foundational figures in literature, philosophy, political theory, history, science, and psychology, spanning from ancient antiquity through modernity.

Here is the total breakdown by source:

St. John’s list - 158 books

Mortimer Adler’s list - 286 books

Harold Bloom’s list - 1,864 books

Theocratic Age (2000 BCE - 1321 CE): 96

Aristocratic Age (1321 - 1832): 229

Democratic Age (1832 - 1900): 345

Chaotic Age (20th Century): 1,194

The three sources above were a good place to start but not always helpful. Bloom recommends Plato’s Dialogues and Shakespeare’s Plays and Poems. Plato’s Complete Works include 36 dialogues and are over 1800 pages while Shakepeare’s works are over 1200 pages with 37 plays. These are more anthologies rather than individual books to read.

In addition, some key authors were missing. No Hesiod, Xenophon, Polybius, from the classical Greeks nor any of the Stoics, such as Epictetus, Seneca or Marcus Auriellius. Key time periods were also under represented. As a Christian, I wanted to see more Early Christian fathers and their writing included. And I was surprised to see only Bloom include Medieval classics like the tales of King Arthur.

The total numbers were also very telling. St. John’s 158 books show what a 4-year focused program can achieve. On the extreme side, Bloom’s list of over 1,800 seems like a ridiculously high number, with over 1,200 books just from the 20th Century. Adler’s total of 286 seemed like a challenging but also possible lifelong number to aspire too. But upon further examination the list wasn’t helpful to create an individual book reading list. Where do you start with these famous classic Greek and Roman writers?

Plato: Dialogues

Aristotle: Works

Cicero: Works

Virgil: Works

There had to be a better source to get a workable reading list.

My list: The 300 Great Books

Collect books, even if you don’t plan on reading them right away. Nothing is more important than an unread library. — John Waters

With these 3 lists as inspiration I began creating my own reading list.

First, I began with the end in mind. I used 300 as the target number of total books.

Why 300?

The number 300 resonates in Western thought through two iconic episodes:

The 300 Spartans at Thermopylae (480 BC): a small, chosen band holding a pass against overwhelming force—discipline, civic virtue, duty unto death, the defense of free polities against an empire.

Gideon’s 300 (Judges 6–8): a divinely winnowed few defeating a vast host—purification, reliance on providence over numbers, moral renewal preceding victory.

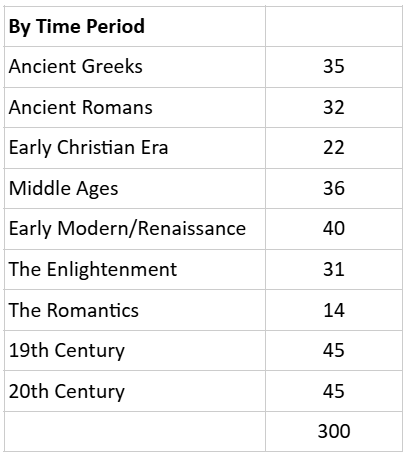

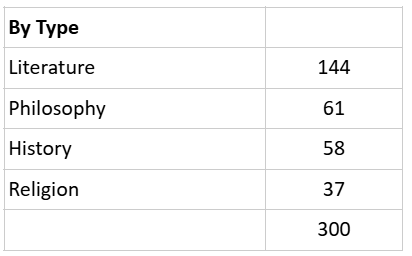

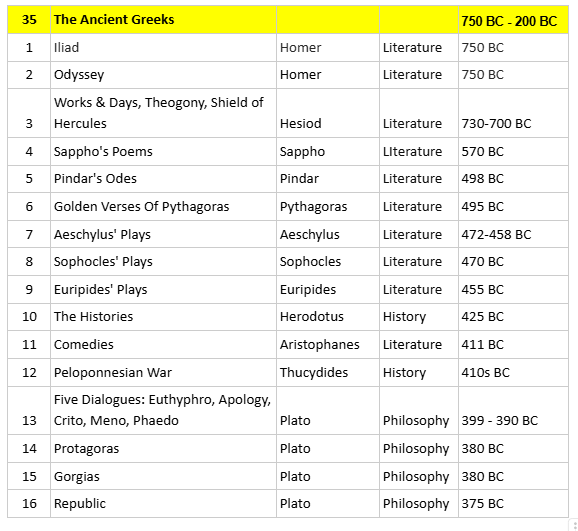

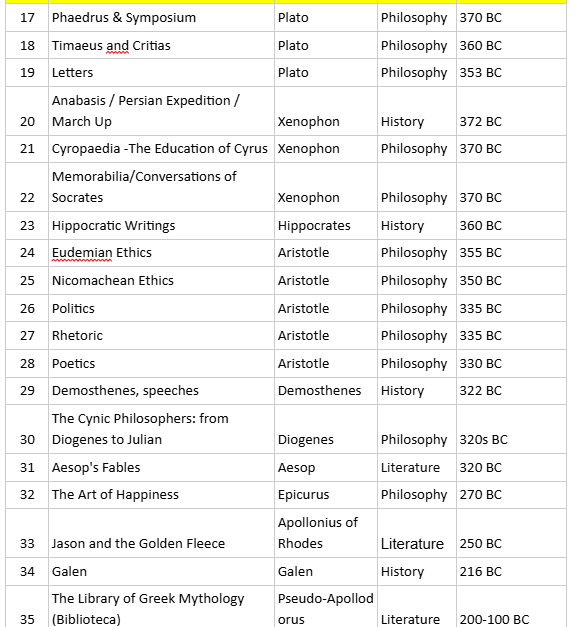

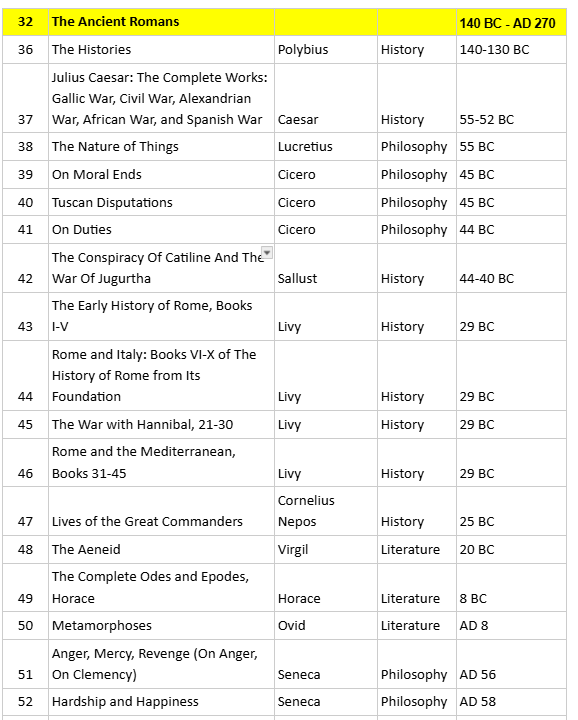

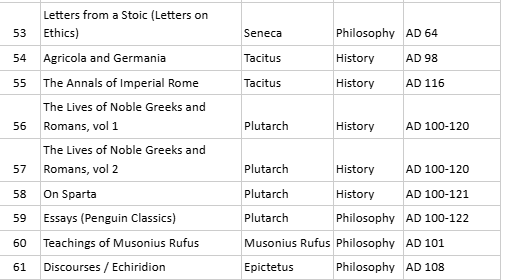

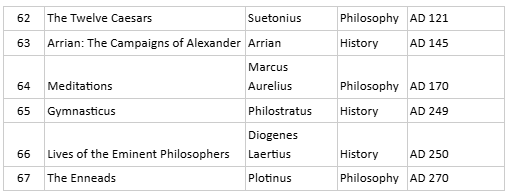

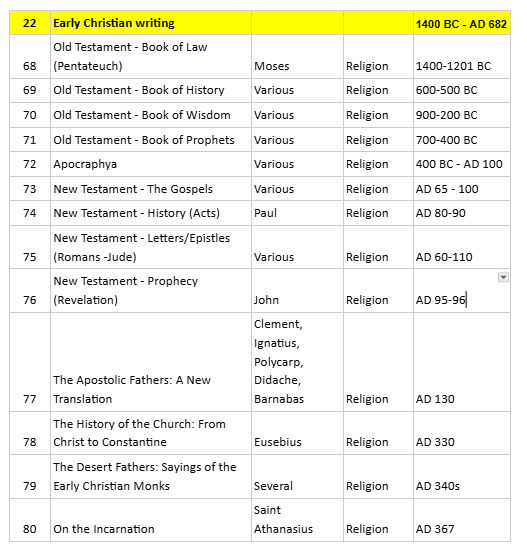

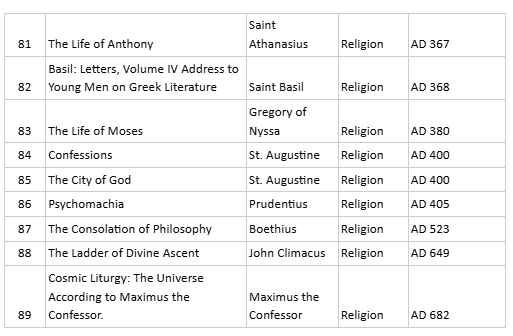

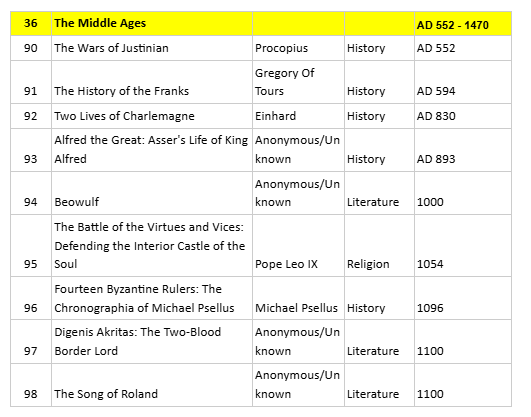

Here is a breakdown of the books by time period and type of book.

A few points of additional insight to better understand my reasoning behind the choices:

Where possible I tried to select individual, separate books. Instead of Homer, I have the Iliad and Odyssey as two separate entries.

Where the main works of an author - such as their poems or plays - could fit into approximately 600 pages I listed it as one entry. For the three great classic Greek playwrights - Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides - we can fit their major plays into one book-length volume.

For most of Plato’s works I have included individual dialogues separately. But where some can be combined, I did that. For example, the first Five Dialogues of Plato - Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Meno, Phaedo - can be read as a book, when published separately was 168 pages.

My list contains more military histories than I found on any of the three sources listed. Part of the bias is due to my military background as a West Point grad and Army veteran. More importantly, there are great lessons of virtue and strategy to learn from the histories of great military commanders like Xenophon, Alexander the Great, Caesar not to mention Plutarch’s Lives and the Roman historians of Livy, Nepos, Tacitus, and Suetonius.

I organized the Bible into distinct books: Law, History, Wisdom and Prophets. I applied this to the Old and New Testament, while treating the Apocrypha as a separate book.

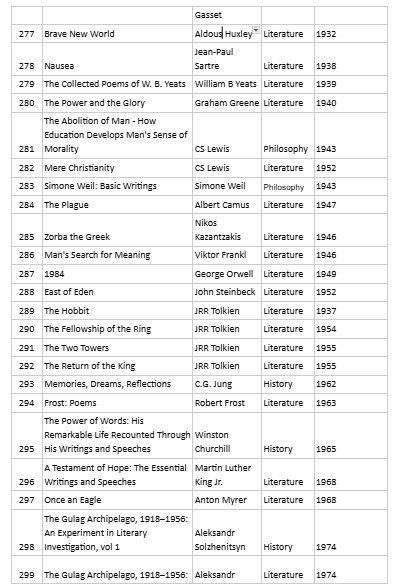

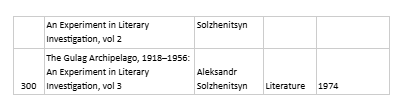

Where singular books are fundamentally structured as three distinct books or volumes, I created three separate entries. Divine Comedy, The Lord of the Rings, and The Gulag Archipelago each consist of three separate books instead of one.

At risk of upsetting literary scholars, I’ve included a number of writing collections that don’t typically qualify as Great Books. We have the writings and letters of a number of famous American and British statesmen. I’ve included these eight collections as separate history books to help benefit from the direct words of these Great Men:

George Washington: Selected Writings

The Essential Hamilton: Letters & Other Writings

Thomas Jefferson: Selected Writings

The Adams-Jefferson Letters

The Writings of Abraham Lincoln

The Man in the Arena: Selected Writings of Theodore Roosevelt

Churchill: The Power of Words: His Remarkable Life Recounted Through His Writings and Speeches

A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King Jr.

Dates are estimates. Where the date is unknown I tried to use the writer’s year of death as an indication.

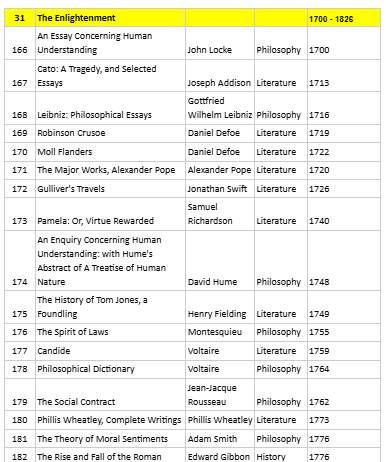

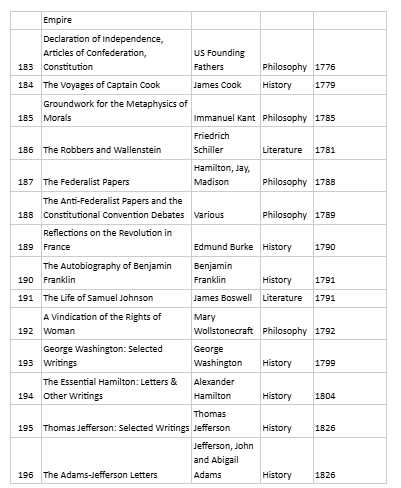

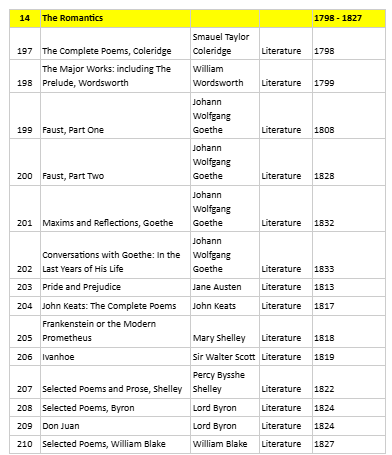

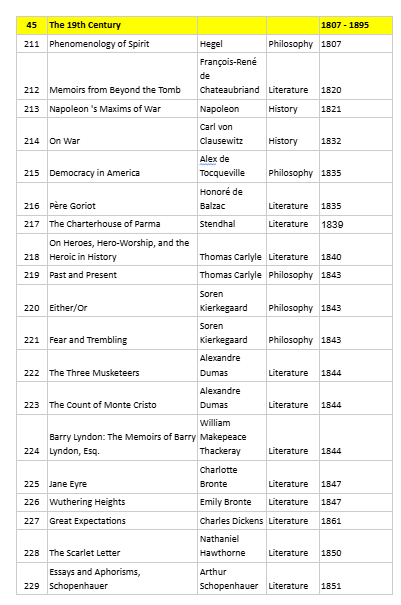

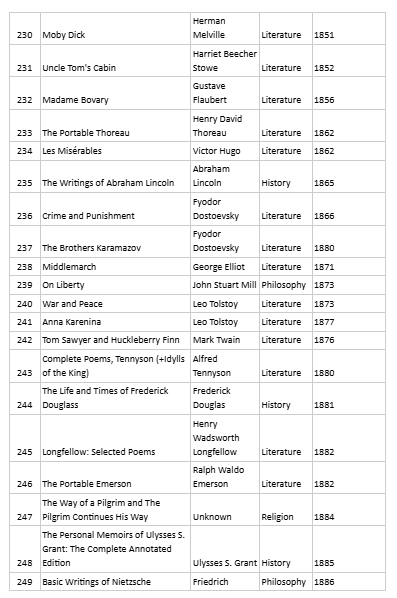

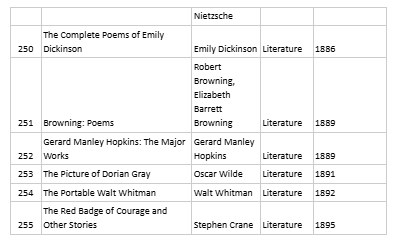

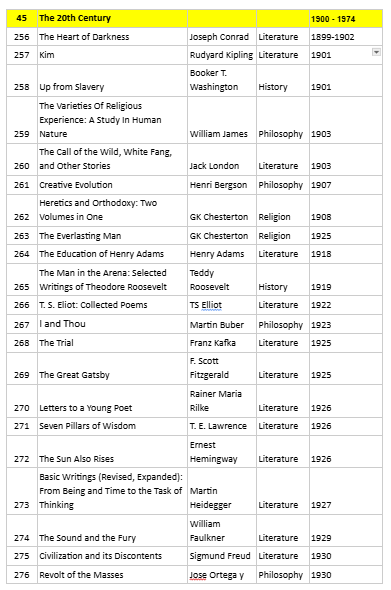

Without further ado, here’s the complete list: A lifelong reading list of the best 300 books of the Western Tradition.

“If you haven’t read hundreds of books, you’re functionally illiterate”- General Jim Mattis

I hope this list has given you Great Ideas for Great Books to add to your reading list.

I want to end by preempting an expected critique of this list. You will find only Western books.

Why aren’t there Eastern books on this list?

I’ve benefited from reading such Eastern classics as Tao Te Ching, the popular Hindu scripture the Bhagavad Gita and excerpts from Confucius’s Analects and the mystical Persian Muslim poet Rumi. But I have limited knowledge of the Eastern traditions. I was raised in a different culture, in a different country.

Mortimer Adler addressed this point better than I can. I’ll leave you with his response to the same question above from his book, How to Read a Book:

We want to mention one omission that may strike some readers as unfortunate. The list contains only Western authors and books; there are no Chinese, Japanese, or Indian works. There are several reasons for this.

One is that we are not particularly knowledgeable outside of the Western literary tradition, and our recommendations would carry little weight.

Another is that there is in the East no single tradition, as there is in the West, and we would have to be learned in all Eastern traditions in order to do the job well. There are very few scholars who have this kind of acquaintance with all the works of the East.

Third, there is something to be said for knowing your own tradition before trying to understand that of other parts of the world. Many persons who today attempt to read such books as the I Ching or the Bhagavad-Gita are baffled, not only because of the inherent difficulty of such works, but also because they have not learned to read well by practicing on the more accessible works—more accessible to them—of their own culture.

And finally, the list is long enough as it is.

Here is to your reading journey, as you explore the perennial questions about what it means to be human.

“The world is a great book...they who never stir from home read only a page.” - St Augustine