The Ancient Athlete Way: Exercise Fitness, Philosophy and Faith, as a Way of Life

Plato’s Protocol Series, 10

And I call on all other people as well, as far as I can – and you

especially I call on in response to your call – to this way of life,

this contest, that I hold to be worth all the other contests in this life.

- Plato, Gorgias 526e

Close the GAP and Cultivate Virtue Daily

To make our program a way of life we need to develop daily habits that guide the choices we make every day. And to inspire us in this practical approach we will look to another famous Greek philosopher, Plato’s most famous student, Aristotle.

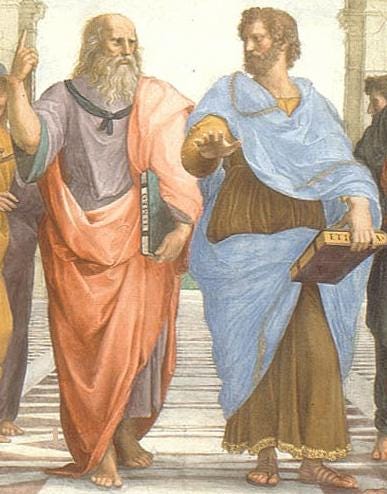

In Raphael’s famous painting “The School of Athens,” Plato and Aristotle are depicted in the center, representing two contrasting but complementary philosophical worldviews. Both teacher and student focus on virtue and wisdom but have different orientations.

Plato is shown as an older man with grey hair, pointing upwards towards the sky. Aristotle, in contrast, is depicted as a younger man with his hand outstretched horizontally towards the viewer. Plato’s main focus is on divine wisdom - sophia - while Aristotle prioritizes practical wisdom - phronesis.

While Plato is known for pointing up - divine wisdom - Aristotle is pointing towards the ground, exhorting practical wisdom.

Plato and Aristotle, The School of Athens by Raffaello Sanzio, Wikimedia

We turn to Aristotle in our last section for inspiration because he describes a type of wisdom concerned with action and decision-making in practical life. Aristotle presents askesis as a methodical, daily practice—virtue is built through action and repetition, not theory alone.

“Virtue is not an innate quality, nor is it simply learned. Rather, it is the result of repeated actions, just as a craftsman becomes skilled through practice. We do not become just by merely thinking about justice, nor do we become brave by discussing bravery. Instead, we become just by performing just acts, temperate by practicing temperance, and courageous by choosing courage when we are afraid. For this reason, it is necessary to make virtue a habit, as we shape our character through the choices we make each day.”

— Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1105b

Let’s look at the timeless workout wisdom we discovered from Plato’s Protocol and see how we can map it into a daily practical program inspired by Aristotle’s cultivation of virtue as habit.

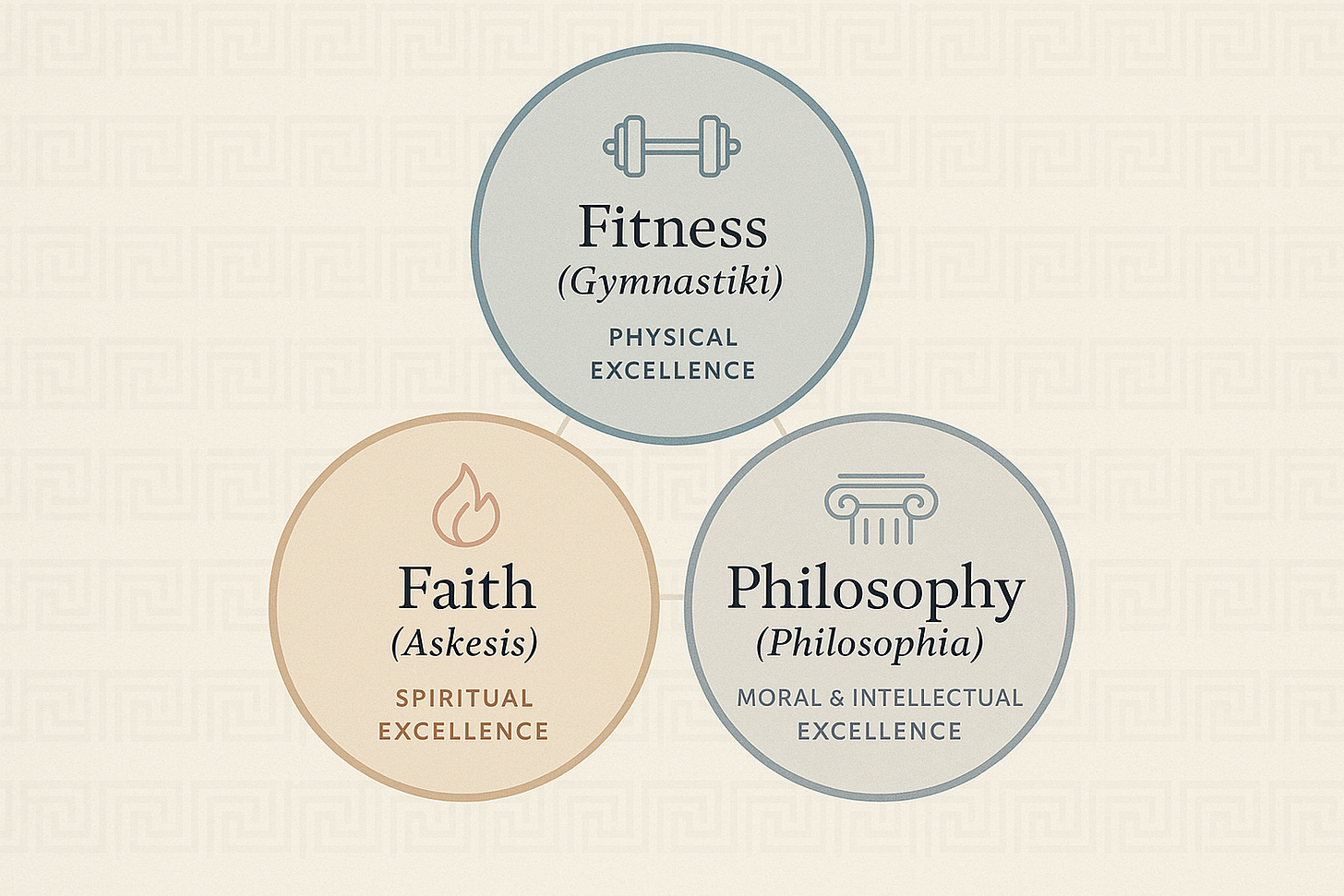

We summarized Plato’s Protocol with three ancient Greek words:

Gymnastiki: physical workout that produces Physical Excellence

Philosophia: cultural workout, the love of wisdom, that creates Moral and Intellectual Excellence.

Askesis: spiritual and philosophical workout that produces Spiritual Excellence.

We can take the acronym this produces - GAP - and use it as a motivational acronym to remind us to close the gap to our highest potential to cultivate virtue - in body, intellect and soul.

Gymnastiiki becomes Fitness, and all the physical protocols that we practice daily.

Askesis become Faith, and the other spiritual and psychological practices to cultivate a healthy soul.

Philosophia is the Greek origin of the word Philosophy and includes other topics in humanities that help us train moral and intellectual excellence.

Exercising Fitness, Faith and Philosophy to Flourish

This last word - flourish - is also a timeless Aristotelian idea. In Aristotle’s most famous book - Nicomachean Ethics - he looks at the virtues and how to apply them to live a flourishing life. Aristotle’s word for flourishing was eudaimonia. This was more than just fleeting happiness or pleasure, but rather a state of living well and doing well, in accordance with reason and virtue.

Eudamonia was about achieving a deep well-being or flourishing in life. Eudaimonia represents the highest good and the ultimate goal of human life. And we achieve that by exercising the virtues - Moral, Intellectual, Spiritual and Physical.

In our program, exercising our virtues becomes a daily workout but also a way of life.

Fitness - Gymnatiski. You practice physical excellence through a daily workout that includes strength training, stamina building, stretching and sports. But also it’s a way of life because you enhance your physical life through diet, supplements and regular labs to test your health and nutrient levels. In fact diet, another Greek word (diaita) in the original meaning represented a whole way of life. It was a healthy lifestyle that was both mental and physical rather than a narrow weight-loss regimen.

Faith - Askeis. You exercise spiritual excellence through your daily practice of self-mastery. Your key capacity is your attention. You are vigilant with your focus. You practice the theological virtues of faith, hope and love through the practices from the bible: prayer, fasting and almsgiving. These three practices are meant to harmoniously work together. Prayer purifies the heart and mind, fasting disciplines the body and detaches from excess, while almsgiving fosters love and compassion toward others. As St. Maximos the Confessor says,

Almsgiving heals the soul’s incensive power; fasting withers sensual desire; prayer purifies the intellect and prepares it for the contemplation of created being. For the Lord has given us commandments which correspond to the powers of the soul. 3

Philosophy - Philosophia. You train moral and intellectual excellence by learning to love wisdom. This is not a passive activity but requires struggle and practice. You cultivate wisdom and develop an awareness of moral excellence through wrestling with the Great Books - the great ideas, events, stories and people of Western civilization. If we are to mirror the education of the classical Greeks - from noble warriors to scribes (people of the book), then we have to imitate the books they created and read. The foundations are the western classics from Homer to the Bible. This contains four categories of books: literature, history, philosophy and religion. From Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey to Herodotus’ Histories, Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War, Plato’s Dialogues (like The Republic) and Aristotle’s Ethics to the Christian Bible. These books became the foundation of the future humanities.

Renaissance scholar James Hankins writes that humanitas ‘’in the widest sense of an education meant to bring out our full human potential, intellectual and moral. ‘’ It was ‘’the belief that certain forms of study—the study of languages, literature, history, eloquence, and above all philosophy—are tools inherited from our revered ancestors that enable us to improve ourselves and the quality of human beings generally.” 4

This study has a practical element for us leaders. The great Greco-Roman philosophers, such as Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics, to the humanistic reformers of the Renaissance, all asked the same question: “What sort of people do we want to govern us?” James Hankins explains they all had the same answer: “We want people to govern us who display moral excellence and have prudentia (phronesis in Greek), practical wisdom, and are thus able to make good decisions for their communities. These virtues are not innate but acquired through study.” 5

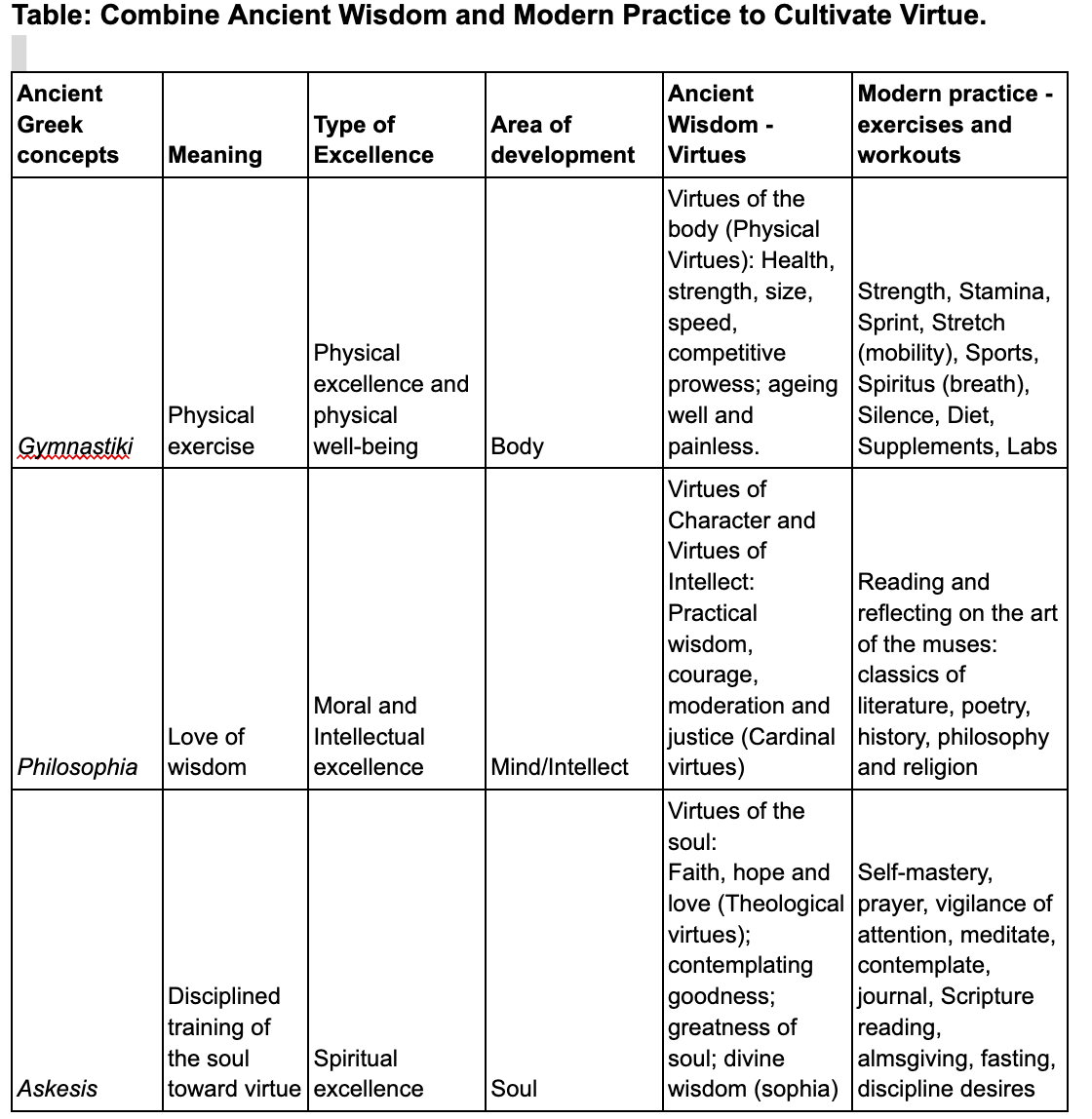

As we close, here is a table that summarizes our programmatic approach to exercising virtue. You’ll see an organized approach that takes you from ancient Greek wisdom to modern practices helping you to cultivate virtue and flourish.

“Never cease sculpting your own statue”

I want to leave you with one final practical concept to embrace in your training. Think of it as a maxim you can call upon as you meet internal and external resistance. As you train daily to close the GAP to your highest flourishing and virtuous self, remember this exhortation: ‘’never cease sculpting your own statue.’’

This inspirational idea doesn’t come from a modern motivational speaker or life coach but from a philosophical descendant of Plato, the Greek philosopher Plotinus. Plotinus (204-270 AD) is considered the founder of Neoplatonism, a philosophical movement that sought to revive and reinterpret Plato’s ideas.

Plotinus has this beautiful passage in his book Enneads. He encourages continuous self-improvement through introspection and continued effort. Plotinus uses the metaphor of sculpting to illustrate the process of refining one’s character and virtues

“If you do not see your own beauty yet, do as the sculptor does with a statue which must become beautiful: he pares away this part, scratches that other part, makes one place smooth, and cleans another, until he causes a beautiful face to appear in the statue. In the same way, you too must pare away what is superfluous, straighten what is crooked, purify all that is dark, in order to make it gleam. And never cease sculpting your own statue, until the divine light of virtue shines within you”

- Plotinus, Enneads I.6 (1)

In Plotinus’ ideal our daily grind can be glorious, as we focus on our inner and outer beauty. ‘’The divine light of virtue’’ is an ideal we all need to embrace. But, channeling Plotinus, we need to realize it will require daily focus in these specific areas:

Continuous effort: This ideal is one of an ongoing process that requires consistent and long term effort.

Targeted refinement: Plotinus suggests focusing on specific areas for improvement, such as cutting away excess, straightening the crooked. For us, we need to identify and work on specific habits and skills.

Self-reflection: Plotinus’ approach involves envisioning an ideal self, to “purify all that is dark, in order to make it gleam.”

Holistic approach: Plotinus’ metaphor encompasses both external actions (chiseling) and internal transformation (seeing one’s own beauty). We need to address both behavior and mindset.

Gradual transformation: The sculpting process implies gradual change over time. We need to understand that our personal growth often occurs incrementally rather than through sudden, drastic changes.

These are great practical principles to embrace externally, in your daily practice, and internally, in the cultivation of your mindset.

Here’s to your embrace of the Ancient Athlete Way where you struggle, in a daily contest for the ultimate prize, your holistic excellence and flourishing.

Remember, ‘’never cease sculpting your own statue.’’

Notes

The Making of a Corporate Athlete Harvard Business Review article, J. Loehr and Tony Schwartz, 2001

H.I. Marrou, A History of Education in Antiquity, p xiv

St. Maximos the Confessor, “First Century on Love” in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume Two. Trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware et. al. (London: Faber and Faber, 1990), 61-2.

James Hankins, Liberal Learning beyond Liberalism: The Humanities as Soulcraft in the Renaissance and Today https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2020/06/64818

James Hankins, Liberal Learning beyond Liberalism: The Humanities as Soulcraft in the Renaissance and Today https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2020/06/64818